|

Dream Bowl - Part Two

by Mike Amen

There may be no

accounting for taste, but the same may not be said for interest. I was

lucky enough to have a nurturing environment firmly in place for a life

of music appreciation, and I think this was helped by other factors as

well. I was born in Napa at Parks Victory Memorial Hospital. I have two

memories of that place. The first is of the ether mask approaching my

face before I went down for the count in which I was asked to engage,

for what was then the near-automatic tonsillectomy that children of

1950s vintage experienced. The other memory, reinforced as I grew older,

was the ghastly architecture of the building. But this was, after all, a

building of function (whose existence was the result of generous efforts

by doctors and concerned citizens), and its less than cheerful facade

was more than offset by the good works happening inside; the stilling of

pain for patients in general, and in particular; assistance administered

to a young mother, my mother, giving birth that fourth day of February,

1947.

With respect to the mystery of why something effects

us deeply, the capacity for enjoyment, and their link to the “...other

factors...” in my own case, I offer the following: I consider myself a

fortunate individual who was twice favored by circumstance. In my

embryonic state, I represented the yet-to-arrive other gender that

families often hope for, in this case the first boy after two girls.

More important, I was the outcome of what must have been, at least for a

time, the happiest of occasions; couples re-uniting after World War II.

And in my father’s case, not only was he happy to be home, but he was

happy to be alive at all. He had fought in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.

That battle, longest in the Army’s history, lasted from September, 1944

until February, 1945. A web site dedicated to soldiers who were killed

or injured there, gave this description: “There was no more deadly fire,

from the viewpoint of the infantry, than that which burst in treetops

and exploded with all its hot steel fury downward to the ground...”

which was exactly how my father was “hit,” and “burst” was the word he

used when he described the event. He suffered serious injury from that

shrapnel, and told me years later that he felt death upon him, and was

certain that had he not fought (digging his fingers into the ground, he

said), he would not have survived. Making matters worse, my mother would

tell me many years later, was the fact that after he received medical

assistance, due to the limited care that was possible, he was not given

a catheter to ward off infection, despite the seriousness of his stomach

injuries, because they just didn’t think he had a chance, and there were

other more compelling injuries on other soldiers needing attention. Yes,

yes, he was happy to be home. To honor his toughness that made life

possible for me, I make a conscious effort to cultivate an appreciation

of life, and while I am a firm believer in personal responsibility for

the development of your own good fortune, I salute with reverence and

humility these facts of formation that lent themselves, I’m convinced,

to cheerful outlook and disposition. I think these bits of fate add good

measure to the psychological endowments and physical apparatus conducive

to music appreciation with which nearly all of us are hard-wired, and by

birthright granted, and which we make use of much of our lives.

So from this beginning of life for

me, if we go five years and ten months to the previous, and on the map,

seven miles to the south, we pinpoint the birthplace of the Dream Bowl.

World War II was uppermost on the minds of Americans during those years.

Hitler’s invasions began in March of 1939. No one knew what the outcome

of the war would be, and there was little cause for optimism for the

nation as a whole, or for individuals. A justifiable reluctance to

involve ourselves in the war, after the tremendous loss of life in World

War I, was removed after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and unfortunately,

regardless of the circumstances bringing it about, the reality of our

involvement could no longer be ignored.

The urgency of the war years brought people together

in a mix of suppressed fear, a desire to keep hope alive, and a real

need to courageously hold one another up. Couples were looking for

something romantic to do with their time because a loved one might be

shipped out the next day, and it might be the last time ever, for them

to be together.

So the initial irony, an

uncomfortable one, that a night club for entertainment and pleasure

begins after bombs fall on Pearl Harbor, is adjusted in our minds

because, as time went on, the value, we could even say the necessity of

such an establishment became more clearly realized. And now we are

seeing renewed interest, dramatically so, in dance. The importance of

such an outlet during the war years (and perhaps now too with economic

and other woes) where one could come; to hear music, to dance, to

congregate with friends, to have our minds taken off the horror of war,

cannot be overstated. For that we owe a debt of gratitude to Gene

Traverso, and John Zanardi. To this can be added the dollar and

cents realities. The partners intended to make money, but this was

bargain entertainment at its best. The History of Vallejo Musicians tell

us that: “Admission was $1.10 with ladies and servicemen admitted for 55

cents...” It should be added that this is before TV had become the

entertainment fixture we now know it to be.

The building is still standing, is still in use, and

I find this to be a very satisfying state of affairs. The fact that it

still stands, speaks to the stability of its original construction. Gene

Traverso, the son, would tell me that, so solid was the foundation and

flooring, that years later, tradesmen would observe that it was

sufficient in strength to support a second story, if one was wanted.

With ease then, did the floor support the step and stomp of dancers, and

its smooth wood finish, allowed for, if you had it in you, the graceful

sliding of feet, and the swaying of bodies. The music propelled dancers

of every sort, in this acceptable means by which young men and women

could touch one another, and so the gliding of couples, the sliding of

soles on maple, would last, in one dance form to another, from 1941

until 1970.

And “standing” is an important

operative word as I recall the beginnings of what turned out to be a

deep-seated curiosity. As I mentioned, because of our frequent trips to

Vallejo, I had many opportunities to notice the Dream Bowl standing in

that field. The stretch of land where it is located is roughly a right

triangle. Think Frank Ghery rather than Euclid. It has a base 1/5 of a

mile at its southern end, its long side along Kelly Road and is exactly

one mile, and the remaining side along Hwy. 29 is .7 miles. As a ten

year old with the not-yet-clogged avenues of youthful consideration, I

was free to absorb all that came through a passing car’s window, and

with each passing, the impression became more firmly impacted in my

mind. If something had gone on, what had that been? Why had it stopped?

The Napa Register article by Pam Hunter refers to a (nine year) “lull”

between the close of the Swing era, and the country/western beginning.

For me, that would have been ages 7 thru 16 (an eternity) during which

there was not a lot of events scheduled.

All these sightings from the car happened during the

day however, and not available was any concept of a night life during

which the club would come alive. John Zanardi’s daughter Louise told me

she remembers helping her father as a young girl, hang posters to

advertise upcoming shows, and I do recall two rare sightings of such

posters: one for Fats Domino, and another for Johnny Cash

hung on telephone poles near the venue. Still, long stretches went by

with no name on the marquee, whose vacancy sadly dramatized the

inactivity of this one-building ghost town. And this building, this big

white building with no neighboring structures, and not even much in the

way of vegetation to compete with its presence, dominated the landscape

and begged a lot of questions. Pick your sentiment; the building these

days is no longer alone in the field or it has lost its singular status

as some sixteen other structures now fill up the triangle. As for the

structure itself, it has been remodeled inside and out so that its

recognition requires the eyes of an archeologist. The changes outside

call to mind a face lift worn uncomfortably. More troubling are the

sensible renovations inside going from dance floor to a series of office

cubicles of low ceiling. New flooring covers the old, which I assume

with hope remains just beneath the surface, and except for a small

maintenance section at its southern end (where bands once set up) its

impressive high ceiling is hidden from view.

About the time of my graduating from

high school (1965), my mother remarried. My stepfather, George, a very

decent and generous man, had lived in a house where Kelly Road

intersected with Hwy. 29. As their marriage approached, he had a new

home built on that same property which was very close to the Dream Bowl.

Because of its closeness to both a major road and a highway, it was not

uncommon for motorists needing direction or experiencing car problems,

to pull off near the house and ask for help. On many occasions, George

would give someone a helping hand, and get them back on the road. In

other cases, the needs of motorists were more unusual, such as the time

impatient inebriants needed soft lawn for a position of compromise. A

safe guess is that they were heading to Napa and all of a sudden it

seemed too far away, and when they had pulled over in their compact car

it more than lived up to its description. George got them back on the

road too, shooing them away like intruding strays.

And so it was, from this eventful intersection near

the Dream Bowl, by which I had passed as a youngster, and to which my

family was now in permanent proximity, that a few more pages might be

gleaned for its story. And if the mystery of its existence was not

intriguing enough, then how about the name itself?

The name is so captivating, such an

inviting enchantment. Who wouldn’t want to go to the Dream Bowl? Who

knows, if you just go to this dance, maybe some magic would actually

take place, and you would in fact meet that girl or boy of your dreams.

My own mother recalled a bittersweet story of an elderly couple who came

to the house inquiring about the Dream Bowl. They were dressed very

nicely, and my mother’s sense of it was that they had come to recapture

a lovely evening shared there many years ago, and they were quite

disappointed to find it closed. Louise (Zanardi) told me that it was

true for many a serviceman from all over the country (but now stationed

in the region), that they would meet girls at the Dream Bowl and for

that reason would wind up settling down here to begin a life with their

sweetheart. If the notion of meeting someone at a dance was not already

a standard feature in the psyche of most people, there was no shortage

of effort in moviemaking or songwriting to place it there permanently

during the 30s and 40s, and it didn’t end there.

In the 1942 movie Orchestra Wives, Paula Kelly

and the Modernaires ask Tex Beneke, the musical question in the verse to

I Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, lyrics by Mack Gordon, music by Harry

Warren :

Hey

there Tex, how’s your new romance

The one

you met at the campus dance

In the 1953 musical, My Fair Lady, Julie

Andrews sings, from I Could Have Danced All Night, lyrics by Alan

Jay Lerner, music by Frederick Loewe:

I could have spread my wings

And done a thousand things

From the 1960 hit, Save The Last Dance For Me,

lyrics by Doc Pomus, music by Mort Shuman,

The Drifter’s (who did Up On The Roof) sing:

But don’t forget who’s taking you home

And in whose arms you’re going to be

So darlin’

Save the last dance for me

And from the first track of their December 1963 debut

album, Please, Please Me, music and lyrics collaborated on by

McCartney and Lennon, the Beatles sing:

Now I’ll never dance with another

Since I saw her standing there

Each of these songs became extremely

popular. Kalamazoo was a #1 hit, My Fair Lady was

successful on Broadway, and later as a film, and I Could Have Danced

All Night, was recorded by many artists. Save The Last Dance,

also recorded by many singers, was recognized as being in the top 25 of

all time popular songs, and one of many written by the great Doc Pomus.

And the placement of I Saw Her Standing There, at the very

beginning of the Beatles’ recorded legacy, speaks for itself.

From the PBS

documentary Ken Burns Jazz, a woman, a dancer, recounts a

uniquely exciting and life-changing moment, one of many uplifting

stories in that series, when she was swept off her feet literally, as

she stood eagerly outside a ballroom, by an adult who snuck her in as it

were, because she was too young to be admitted by the normal means. She

was then provided a breathtaking look at the experience in full swing as

she was quickly transported around the room in dance, and escorted,

aloft practically, in her now elated state back out to the front of the

ballroom, and to the world outside. And very little of the excitement

was lost in its re-telling, because you could see the animation, the

excitement in her beatific smile, as palpable now, as it must have been

then. What a wonderful thrill. What do you say? Come on, let’s go

dancing. Let’s go to the Dream Bowl.

It had always been the case at the Dream Bowl that it

was a venue where you could see local bands along with those of national

prominence. Love of music, and its appreciation, brought together a wide

variety of individual band members and fans all circling around one

another in a weave of living stories.

Babe Pallotta Band performing (circa

1950) from

www.smythesaccordioncenter.com

One such local

musician was Babe Pallotta. He was the first musician I spoke

with who had performed there during the Swing era. I had the privilege

of meeting and talking with Babe about his musical career, shortly

before his passing in May of 2006. When I met him, he had respiratory

problems, and had to use oxygen, but otherwise seemed perfectly fit,

with lively, intelligent eyes, good cheer, and gentlemanly manner. Later

I would see pictures of Babe when he was in his twenties, and it could

be seen that he was a handsome man, who had preserved those handsome

features and pride in appearance. He dressed sharp, and still had some

dark strands of what must have been, when younger, a head full of

jet-black hair. He told me he began playing accordion when he was eight

years old. Several relatives helped him learn music, including his

father who also played accordion. He would eventually join his older

brother Joe, a drummer, who had formed his own band. According to the

History of Vallejo Musician’s, Joe tried to earn a spot in the Al

Chester Band from his home town of Crockett. “Trying out for this group,

Joe was told he played too loud, and being miffed, decided to organize

his own band, using his relatives to form a combo.” Over time, this grew

to a twelve piece orchestra, for whom, “Work was sporadic at first, but

by 1941 the orchestra started a 25-year run of steady work, an

incredible record for a local band.” An interesting tie-in to Napa and

Vallejo histories is the fact that Babe, as reported in the Times

Herald, played baseball for the Napa Merchants in 1942 before being

drafted into the army. He also played at the Turf Club at Candlestick

Park during the eighties. Babe told me that playing in the Joe Pallotta

Band for a time was the unique guitarist Roy Rogers, who played

with Blues great John Lee Hooker, who, towards the end of his career,

made his home in Vallejo. Also spending time in the Pallotta band was

trumpeter Marvin McFadden, another Vallejoan who has played with

Huey Lewis and the News.

In the quest for this story, and the finding of

facts, I was first led to Guido and Rosey Colla. Mr. and Mrs. Colla and

my mother were friends. They ran into one another at a restaurant, and

by mysterious chance, the Dream Bowl came up in conversation. My mother

knew I was interested in writing on its history, and she arranged a

meeting at her home, and we got together for an enjoyable talk about

their recollections. I shall be forever grateful for this circumstance

as it generated much that would follow in the unfolding of events.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell often quoted the ideas of Arthur

Schopenhauer, and from an interview with Michael Toms recounted in the

book An Open Life, Campbell says:

There’s a wonderful paper by

Schopenhauer, called “An Apparent Intention of the Fate of the

Individual,” in which he points out that when you are at a certain age -

the age I am now (his 80s) - and look back over your life, it seems to

be almost as orderly as a composed novel. And just as in Dickens’

novels, little accidental meetings and so forth turn out to be main

features in the plot, so in your life... And then he asks: “Who wrote

this novel?”

So, continuing in this regard, here we go. The night we met, Guido and

Rosey told me they went to the Dream Bowl during their courtship, and

they suggested I contact Babe, whose name we found in the phone book on

the spot. Their son, Johnny Colla, was an original member of Huey

Lewis and the News. On Feb. 7, 2008, my wife Sylvia and I attended a

Vintage High production of Miss Saigon, in which our granddaughter

Caylie sang and danced. In the pit orchestra was none other than Marvin

McFadden on trumpet and flugelhorn. Caylie’s father, Mike Soon, is a

chemist working for Caltest, an environmental testing company who house

their offices in a building where, once upon a time, music and dance

took place. They called that place the Dream Bowl. Now ain’t that an

amazing little swirl of people and places?

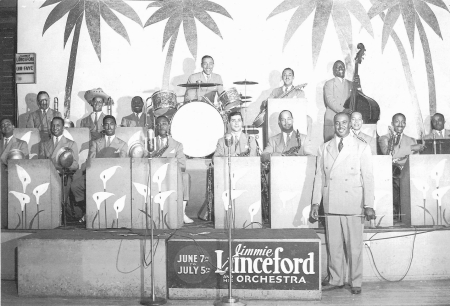

Jimmy Lunceford and his Orchestra.

Babe told me, that

at some point, the band won a competition, and became the “house band”

for the Dream Bowl. I asked him about his own recollections as a

listener. Were there bands that performed at the Dream Bowl that stood

out? The band that impressed him the most was Jimmy Lunceford and his

Orchestra. His face became more animated as he thought back. He

mentioned that the musicianship was of very high quality, as was the

presentation.

In an essay by critic and author Ralph J. Gleason, he

had this to say about Lunceford: “The songs were all played, regardless

of their simplicity or complexity, for dancers, basically. After all,

these were dance bands and, except for its one brief tour of

Europe just before World War II broke out, I doubt if the Lunceford band

ever played a concert. They played dances and they played stage shows;

the concert era for big bands came a good deal later.” It was a great

pleasure to discover that Gleason, a man whose work and person I greatly

admired, had written about Lunceford in Celebrating the Duke an

excerpt of which was included in Reading Jazz. As a college

student, a fellow student had played him a Lunceford recording, and he

flipped, becoming an instant fan. The passion for the music, so strong

at that age, comes right off the page:

They used to appear on

blue-label 35-cent discs every couple of weeks at the bookstore

on the Columbia campus – two sides, 78 rpm, and you had to be

there right on time or the small allotment would be gone and

you’d have missed the new Jimmie Lunceford record. If you were

lucky you got one, ran back to your room in John Jay or Hartley

Hall, sharpened your cactus needle on a Red Top needle

sharpener, the little sandpaper disc buzzing as you spun it, and

then sat back in ecstasy to listen to the sound coming out over

your raunchy, beat-up Magnavox.

Ah, that sense of urgency is such a wonderful thing.

For that reason I want to say some more about Gleason and why I

respected him so much. Gleason’s work would be of considerable

importance as he seemed to be on the vanguard, and able to tap into and

accurately report valuable changes as they unfolded. For me he was a

reliable guide for those things that proved to be worth while, and was

exemplary in the appreciation and celebration of music. I started

subscribing to the jazz magazine down beat, in 1964, and before

that was buying it off the rack. Gleason was a regular contributor to

the magazine, and I always found his work worth reading. In the early

60s, he hosted a quality TV show called Jazz Casual on PBS, and

later in his career was co-founder of Rolling Stone magazine.

Especially endearing for me, was the fact that he was one of the

first, if not the first jazz critic to take seriously the things

that Rock bands were doing, and there was many an aspiring musician,

particularly in the Bay Area, who deeply appreciated Ralph’s influence

in bringing respectful consideration to what they were doing. I was

still interested in jazz, but was becoming equally interested in Rock,

and I can assure you, there was considerable snobbery in evidence in the

jazz press.

You could gather from Gleason’s

reviews, that he was a careful listener, and this was further evident in

the respect he had earned in the musical fraternity. A footnote lends

yet more evidence from an experience talked about by Steve Allen during

his on-camera musings as he was bidding farewell to his pioneering place

on late night TV. More than any other host of his time, Allen, a

musician himself, was interested in and supportive of musicians, and his

show was always a haven for unique musical presentation. I recall, for

example, a show on which Henry Mancini was a guest for the entire night,

and on that same show, the very talented Cannonball Adderley Quintet

performed, after which Mancini gave great praise. I thought to myself at

the time, we sure could use more shows like this. I say this because

that sort of public validation for jazz musicians from a respected

member of the music mainstream, seldom occurred. Despite Allen’s own

skills as musician (he could play anything), he was still known as a

funny-man, and because of that had always been automatically, and

unfairly snubbed by the critics. To prove a point, he contrived a hoax

he fully intended to reveal, and made a recording of jazz piano pieces,

overdubbing as it were, a third hand. For the liner notes, he invented a

person with an intriguing biography: a reclusive black pianist just

recently discovered, and here now, for the first time, were the

recordings. The record received splendid reviews, and the wool had been

successfully pulled until Ralph J. Gleason listened to it, and heard a

few too many notes happening for two hands, saving Allen the trouble of

revealing it himself.

As for my own youthful urgency, when my interests

shifted from my baseball card collection to down beat magazine,

it was with great anticipation and hope that I went to the corner of

First and Coombs in downtown Napa, where a magazine rack was located in

front of the drugstore, one of the few places in town the magazine was

available, and where they too had a small allotment. I clearly remember

my steps quickening with greed as I neared the corner. Let me not be

late; just one more issue for yours truly, if you please.

As can be seen, it was modest

equipment for Ralph J. Gleason too, and this is a decade and a half

further back in the dark ages of sound reproduction. Still the ideas

were sufficiently conveyed so that the “ecstasy,” was experienced.

Enthusiasm for the essence of the musical message is useful in hearing

past the scratchiness of a poor recording. I’m reminded of comments

(during an interview with Grateful Dead Almanac editor Gary

Lambert) by mandolin virtuoso David Grissman, who along with Jerry

Garcia (who would become the lead guitarist for the Grateful Dead)

immersed themselves in bluegrass one season, going to music festivals,

and always seeking that rare recording that captured something great.

Grissman described some of those rare recordings as “...sounding like

frying eggs.” If you grew up in the fifties, you know that sound.

Recording technology was not an issue however, where

live performance was concerned. With respect to the Jimmy Lunceford

Orchestra, the theatrics were impressive, choreographed in precise

manner, and delivered with great flair, but the music never suffered as

a result. No matter what acrobatic feat the musicians were up to, the

music still cooked madly. Lunceford himself was a man who seemed

perfectly suited to be a band leader. A large man of fairly serious

comportment, he was the calm center against the sometimes frenzied

activity that surrounded him. The baton he used to lead the band was

oversized and caught one’s eye as did much of what went on with this

band. The drummer was up front, in the center, and on a raised stand,

which was equipped with what was, for its day, an extravagant drum kit.

Every bit of it got used with crossover moves and stick tosses that

added punctuation to the musical statements being made by the band, and

yet the drummer’s contribution was a show all by itself. There was so

much going on that it wasn’t until a third or fourth look at a You-Tube

video clip that I saw the amazing things the drummer was doing. Gleason

goes on to say, “…maybe they would do ‘For Dancers Only’ for half an

hour…making the whole audience meld together into one homogenous mass

extension of the music.” Sounds like the stuff of a memorable evening.

Horace Silver

Pianist Horace Silver who

successfully blended blues and Latin rhythms in his unique and varied

compositions which pleased both musicians and audiences alike, credits

The Jimmy Lunceford Orchestra with helping to cement his decision to be

a musician. Silver writes about this in his autobiography, Let’s Get

To The Nitty Gritty, but I first heard an account of it, from Silver

himself, on KCSM’s Jazz Profiles which is hosted by Nancy Wilson. He

said his father took him to Rowayton, Connecticut “...almost every

Sunday to Rowton Point.” His mother had passed away when he was nine and

now he was eleven. It was an amusement park and they’d eat hot dogs, and

ride the rides. On one of these occasions, “Jimmy Lunceford and His

Orchestra come up on a Greyhound bus. (It said so on the side of the

bus) I said, ‘Dad could we please stay to hear one number.’ “We waited

half an hour or forty minutes just waiting for them to get set up at the

dance pavilion.” He goes on to say that “...blacks were not allowed

inside at this time.” The pavilion was not totally enclosed, so you

could stand nearby, hear them and see a little. “They started playing,

and the music sounded so good. The Jimmy Lunceford band was so together,

they were hitting it so precisely, and the music was swingin’ and it

sounded so good. I begged and pleaded with my Dad to stay for one more

tune, and we stayed for three or four tunes.” “It was when I heard that

Lunceford band, that’s when I said to myself that’s what I want to be: a

musician. They were dressed nice, the singing was good, the playing was

good. It was just one hell of an outfit, and that’s when I made my

commitment to be a musician.” As he was recounting this, I could hear

the excitement in his voice echoing the impression they had made, which

reminded me of the enthusiasm I witnessed in Babe Pallota’s face when he

talked about how great they had been. For Horace Silver the depth of

that impression was reflected in the serious tone of his voice at that

moment, and borne out by his compelling compositions, energetic soloing,

and the successful and influential career that followed.

There are many stories about individual musicians,

and bands of all types, big and small, who play all manner of music,

that for one reason or another, never got the recognition they deserved.

The Jimmy Lunceford Band, although well-known, probably should have been

more celebrated than it was.

As regards the Lunceford band, and

the performing style of the time, Ralph Gleason added this:

True big band freaks, of whom I was one, were

absolutely dedicated to the Lunceford band. It had – and still has –

a very special place in the memories of those who date back to the Era

of Good Feeling of the 30s, when the big bands symbolized a kind of

romance and glamour and exotic beauty long gone from the world of

entertainment...and when I got to the Big Apple and found that you could

actually get to see a band like this in person at the Apollo or the

Savoy Ballroom or the Renaissance or the Strand or Paramount theaters, I

simply couldn’t believe it. It was just too good to be true.

And for people from Napa, and Solano

counties, the Bay Area and beyond, the Dream Bowl was that place where

those same bands and performances could be experienced, and where one

could be part of what was “just too good to be true.”

__________________________________

© Mike Amen 2010

Yours truly and

sister Lynda dancing, circa 1959. Out of the frame is big sister Paula

offering instruction. Note “Hi-Fi” unit between chairs. |