MARK STOCK: MARK STOCK:

PORTRAIT OF A FRIENDSHIP

The

piece below, by New Mexico-based artist Elizabeth A. Kay, offers

a very personal insight into the life of the wide-ranging, artistic tour

de force Mark Stock, who passed away in 2014 at the age of 62.

Though not a native Californian, Stock had a high profile in a variety

of artistic communities on the west coast. He was a brilliant

lithographer and painter who distinguished himself as an artist, after

printing for some of the greatest artists of the 20th Century. His

painting "The Butler's in Love" hangs in the legendary San Francisco

restaurant Bix, where it captures a certain strange aspect of the

character of The City, where style, mystery, and esoterica feel native.

Mark was an actor, engaged in performance art in Los Angeles, as well as

a talented magician who dazzled audiences in Los Angeles and San

Francisco. Mark was a champion amateur golfer, and also a gifted

musician, a drummer who began playing with rock bands as a kid and then

later became a jazz drummer. Mark played for a time in the trio

of Bay Area sax stalwart Jules Broussard, though Mark's life partner

Sharon Ding says "the

two musicians who Mark credited for teaching him his jazz chops were

pianist

Tee

Carson and bassist John Goodman. Mark played in Tee’s

trio for many years during the 1990s in San Francisco," before a long

stint leading his own Jazz unit.

In

this long and touching piece, Ms. Kay details her lifelong friendship

with Mark, which began at the University of South Florida in the 1970s,

when both young artists were inspired by master lithographer Theo

Wujcik. Her story is a fascinating look into the life of an artist,

his and hers, and will certainly resonate with readers who have traveled

similar paths.

Elizabeth A. Kay's paintings, which offer a whimsical take on

traditional southwestern American iconography, have been exhibited in

the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, in the New Mexico

Museum of Art in Santa Fe, and elsewhere. One of her works appears in

the recently published Georgia O'Keeffe, Living Modern by the

renowned art historian Wanda M. Corn (Brooklyn Museum - Delmonico Books

- Prestel. 2017) who writes - "Referencing pop culture and employing a

regional vocabulary...Kay's portraits of O'Keeffe capture the reductive

and commercial nature of celebrity in contemporary American culture."

Like her lifelong friend Mark Stock, Elizabeth is also a musician - a

pianist and singer.

_________________________________________

In

January as I was cleaning out some old files, I found a trove of

letters, photographs, articles and emails that my friend Mark Stock

had sent to me between 1978 and 2010, along with a stack of show

announcements from his San Francisco gallery Modernism. His work was

exhibited there regularly, until his death in 2014 at age 62. January

being bitterly cold, I holed up in the studio, lit a fire, and for the

next few days read through the hand-written letters. Then I spread

everything out on the drawing table and began to organize the materials

into a folder. At the same time, I emailed Mark’s partner, Sharon

Ding, asking if she would like the folder for his archives, and was

delighted when she responded enthusiastically. As I organized the

letters and announcements by date and inserted them into plastic

sleeves, I knew that the time had come for me to write something about

my unusual, gifted friend whose life had ended so suddenly.

Mark and I met in 1974 in a

lithography class taught by Theo Wujcik at the University of

South Florida in Tampa. We were two undergraduate art students working

towards B.F.A. degrees. Several years my senior, Mark was a slender,

blond, good-looking young man of 23. Other students in the litho class

were John Ludlow, Wendy Meyerriecks, Arnold Brooks, Judy Jaeger, Bill

Masi, Richard DuBeshter, and Bill Volker, many of whom Mark

wrote about in his letters. A mutual friend named Cynthia Zaitz

was also mentioned, although she was not part of our class.

Wendy Meyerriecks introduced

me to lithography. After graduating from the same high school in 1972,

we enrolled as fine art majors at USF, a vast campus whose student body

numbered about 17,000 and was growing fast. For the first year, I

concentrated on painting, drawing and design classes, along with other

requirements. Then one afternoon Wendy brought me into the litho shop,

put a grease pencil in my hand and encouraged me to draw on the smooth

surface of a limestone block about the size and thickness of a

dictionary. I have had a couple of epiphanies in my life and this was

one of them. As I felt the point of the pencil drag across the polished

stone and saw the sensitive line it made, I knew I had found my medium.

Lithography had been invented in 1796

by Alois Senefelder (1771-1834), a young German author and actor

with a background in chemistry, who was looking for an inexpensive way

to duplicate his plays. One day as he jotted down a laundry list with a

grease pencil on a piece of Bavarian limestone, he was struck with the

idea that if he etched the stone the grease markings might remain in

relief. Two years of experimentation later and Senefelder had invented

the technique of lithography— a process that would revolutionize the

printing industry. So long as the etched stone was kept wet the grease

marks could be repeatedly inked and printed in large quantities.

Senefelder documented his discovery

in a book called “A Complete Course of Lithography,” which was

translated into French and English. The new process became an instant

success and was first used to duplicate sheet music and prayer books.

Artists quickly caught on to the infinite range of tones, textures and

lines that could be drawn on the stone. By the 1820s, lithographs of

people, scenic views, and expressive flights of imagination were being

marketed individually, or sold as portfolio sets and book illustrations.

All the great artists of the 19th and 20th centuries made lithographs:

Géricault, Delacroix, Whistler, Daumier, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Redon,

Matisse, and Picasso among them. In the late 1900s another boom occurred

with the production of colorful mural-size theater posters.

I discovered that I loved everything

about the complicated, physically demanding process, from the fragrance

of the buttery inks, to the strength it took to polish limestone slabs

using water, pumice grits and a heavy, hand-rotated levigator. I even

loved the smell of nitric acid poured drop by drop from a glass beaker

into an ounce of gum arabic, though the fumes burned my nose. The shop’s

fork lift was designed to move big stones from table to press bed, but I

took pleasure in testing my strength by carrying medium-sized ones.

Lithography was the messiest process imaginable, but if properly done it

yielded a uniform edition of pristine, hand-made works of art.

Unlike the solitary business of

painting and drawing, the litho shop, though by no means large, was a

communal space where I could work on my art, learn from my peers, or be

amused by them. Men outnumbered women, but not by much, and everyone in

our class had a wry sense of humor. Personalities began to distinguish

themselves. As I meticulously drew surreal subjects on stones, ranging

in size from 11” x 14”, to 20” x 24”, I noticed that Mark Stock was

already maneuvering 30” x 40” stones. Mark was constantly exchanging

quips with John Ludlow, who worked for the City of Safety Harbor

and whose cartoon-style drawings matched his down-home wit. Bill Masi was a thickset young man with a trim black beard and long pony tail

who worked at the Tampa Tribune. Judy Jaeger was a pleasant

married woman a bit older than the rest of us. Arnold Brooks looked and

mumbled like Bob Dylan, and Bill Volker was secretive behind his

John Lennon shades. Wendy and I were the youngest members of the class,

but just as determined as everyone else to master lithography.

I didn’t know it, but lithography had

been enjoying a renaissance in the 1960s and ‘70s, and it was just dumb

luck that we students were working in a cutting-edge center for the

medium. When our instructor, Theo Wujcik, wasn’t teaching or making his

own art he was printing editions for artists at Graphicstudio, a

professional atelier connected to our shop. Visiting artists like

James Rosenquist, Robert Rauchenberg, Shusaku Arakawa, Ed Ruscha, Larry

Bell, Richard Anuszkiewicz, and Jim Dine were making prints

just a few yards down the hall. As I walked to class I could see their

proof prints tacked on the walls.

I was taking a full class load each

quarter, trekking across the sweltering campus, arms loaded with books.

But I came to regard the litho shop as home-base, a place where I could

rest between classes, work on my latest print, and visit with friends. I

noticed that Mark was always in the shop working on a print, even during

school breaks when few people were around. While the rest of us

struggled with the complicated medium, he mastered it quickly and was

soon pulling large, spectacular prints off the biggest limestone slabs.

He and Theo began to set a standard of excellence that was influencing

the rest of us. Theo was as excited by Mark’s prints as Mark was and

helped him at all hours to achieve success. At night I watched the two

of them bent over the press, Theo swiping away wayward flecks of ink

(“scum puppies,” we called them) with a wet sponge, as Mark rolled ink

onto the image. John Ludlow, who was struggling with a print run at

another press, suddenly bellowed in his rich southern drawl, “Scum puppy

be-GAWN!” which made us all laugh.

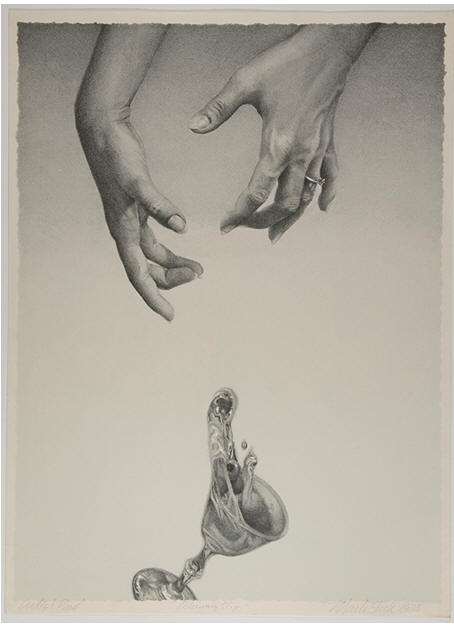

Mark loved working with the human

figure and quickly found subject matter literally at his fingertips. He

photographed John, Richard and Arnold and then drew large, realistic

portraits on stone with litho pencils that he kept sharpened with a

single-edge razor blade. When a drawing was finished he chemically

processed the surface of the stone with gum arabic and nitric acid,

washed away the residue with solvents, recharged the drawing with

asphaltum, wetted the stone, and inked the image with a large roller

charged with black ink. I still own the portrait he did of a laughing

John Ludlow, as well as a lithograph he made of my hands with a martini

glass falling out of them titled, “February Slip.”

I was in the shop one day when Mark

was printing one of his big portraits. He had worked countless hours on

the drawing and was in the process of pulling an edition of ten prints.

The limestone slab was on the press bed, Mark inked the image and

immediately wiped the stone with a wet sponge. The thin film of water

allowed only the image area to receive ink, but if the stone dried out

the ink would instantly adhere to the non-image area and the dreaded

“scum puppies” would suddenly be everywhere. Sponging was an art in

itself and master printers always had a sponging assistant. The stone

inked, Mark laid a large piece of Arches White rag paper on top, making

sure the registration marks were perfectly aligned. He then covered the

rag paper with newsprint and a plastic tympan, and lowered the handle of

the press, locking a greased wooden scraper bar onto the stone. As he

smoothly hand-cranked the press bed it moved under the scraper bar,

which exerted enormous pressure across the tympan as it transferred the

ink drawing evenly to the rag paper. The room was quiet, except for the

clanking sounds of the press and the splash of the water bowl. Suddenly

there was a strange “pinging” sound. Mark froze. “No, no, no, no!” he

said under his breath. We rushed over as he removed the plastic and

papers and what we saw made us groan. A hairline crack ran the entire

length of the stone, right through the center of Mark’s gorgeous

drawing. The stone, probably worth $1,000, had just broken. It could be

recut into two usable smaller stones, but Mark’s drawing was ruined.

Anyone else would have scraped that

image and moved on to something else. Not Mark. When I saw him next, he

was polishing another large stone on the grinding table with water,

grit, and the heavy round levigator. That task finished, he transported

the stone with the fork lift to one of the metal tables and began

laboriously making the exact same drawing again. It took time,

determination and grit (pun intended), but in the end Mark got his

edition.

♦♦♦♦

Tuition at USF was amazingly

affordable in the early 1970s; good thing, too, since none of us had

much money. I paid for each quarter with wages I made as a part-time

waitress and still had enough left over for rent and groceries. Mark

didn’t have much spare cash either, and I remember feeling properly

jealous when he told me he had just won $200 in an art contest — big

money in those days. So it was a special treat when Mark, myself, and

other friends piled into our VW Bugs (mine was white, Mark’s a battered

navy-blue) and left campus for lunch at a cafe called Main Street

Bakery. There we wolfed down grilled cheese sandwiches, drank coffee and

listened to Mark rave about his favorite Charlie Chaplin film. Then it

was back to the litho shop to work on our prints, until the building

closed at 11 p.m.

Most students lived at home, in the

dorms, or rented small apartments in the university area. Mark must have

rented an apartment nearby, although I never saw it. I was lucky,

because a friend had invited me to rent several rooms in a grand, if

rundown, country house near the rural town of Lutz. At eighteen, I moved

out of my parent’s conventional home in the suburbs into a truly

marvelous old Florida estate built in the 1920s. The gracious,

red-tiled, Spanish-style house had multiple fireplaces and (it was

whispered by my fanciful house-mates) Scandinavian demonic symbols

painted on its cypress wood ceilings. It also had a secret compartment

in the wall for stashing bootleg whiskey. It was rumored to have been

one of Al Capone’s homes, though I’ve never found any historical

evidence to support this. Shaded by towering pines draped with Spanish

moss, it sat on ten acres of private land surrounded by cypress swamps,

an orange grove and a wide lawn leading to a lake. The first time Mark

came out he fell in love with the house and its romantic history. He

even embellished its sinister past by insisting that a shallow porcelain

tub lying in the grass had probably been used for dissecting dead

bodies. He might even have been right since the house was owned by a

local doctor. One time, Mark brought a friend out and to my astonishment

proceeded to give his captivated audience a thrilling tour of its

history, as if Mark, not I lived there! It was the first time I glimpsed

what a masterful showman and story-teller he was.

As we all became better acquainted we

learned that Mark was not only an exceptional artist but a talented

golfer and a fine musician who played drums, guitar and sang. Being a

guitar player myself, I invited him and Cynthia Zaitz out to my house

where we sang songs by Elton John, Carol King, the Beatles, Buddy Holly,

and the Everly Brothers. Needless to say, Cynthia and I had bad crushes

on Mark, but for whatever reasons nothing ever transpired between Mark

and I besides friendship.

Graphicstudio’s manager, Chuck

Ringness, a man not much older than us, had a gravelly voice and

tended to mumble his words. John Ludlow called him “Arrgh” behind his

back. Chuck brought in a young printer named Patrick Lindhardt to assist

him and as we students became better acquainted with the printers at

Graphicstudio there was some socializing. Over Christmas Chuck invited

Patrick and me to a party at his apartment, where I enjoyed my first

taste of hot buttered rum. Sometime later, when the litho people came

out to Lutz for a party, Chuck and his fiancé brought along

artist-in-residence, James Rosenquist, and his family.

Just before I graduated, Chuck

prevailed on me to let him have his wedding reception in Lutz. I cleaned

the house until it shone, filled several punch bowls with Sangria,

sliced oranges from the orchard, and made avacado hors d’oeuvre picked

from the monster tree growing next to the house. Students, faculty, and

artists began arriving with flowers, food and plenty of liquor. I had

bought a new dress for the occasion — a flowered ’20’s style gown that

flowed to my feet. Mark showed up wearing a colorful jacket, followed by

friends from the litho shop, who turned up in their best clothes to

toast the bride and groom. We sat outside in the generous old patio with

a fire flickering in one of the outdoor fireplaces for atmosphere, since

it was a balmy evening. Candles twinkled and the once-majestic old house

took on a mellow cast, as if it had been waiting a long time for just

such a party. It was a merry time, even as the company went from being

mildly tipsy to seriously so. And if John Ludlow and I went for a

late-night canoe ride on the lake, and ended up tipping over in the

middle and had to swim back in the dark, which pretty much ruined my

beautiful dress, well . . . it was a grand artist’s party and such

things are to be expected.

Mark and I spent two years in Theo’s

classes learning the alchemy of lithography, trying to make the best

prints possible, and rubbing elbows with professional artists. That

heady combination set my life in its particular direction, which up

until then I did not have a clue about. When Chuck Ringness’s fiancé

told me about the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico,

where people trained to become master printers, she had hardly finished

her sentence when I determined that I would move to that city and see if

I could get into the program. And if that failed, then perhaps I could

get into graduate school at the University of New Mexico. With that plan

firmly in mind, I made preparations to leave Florida right after

graduating. Theo wrote a glowing letter of recommendation, ranking me

among the top five percent of all the graphic students he had worked

with over the last ten years. Having worked alongside Mark, I did not

feel that I deserved such praise, but I was deeply grateful for the

letter, which helped open the right doors.

Mark’s masterful prints had caught

the attention of the head of the art department, Donald Saff. After Mark

graduated in 1976, Saff helped him land a prestigious job as a

lithographer at Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles where Mark printed for (and

befriended) the artistic giants of that generation: Jasper Johns, David

Hockney, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, James Rosenquist and Roy

Lichtenstein.

In June of 1975 I packed my print

portfolio, clothes, and a few kitchen supplies into my VW and drove to

Albuquerque, followed by my friend Cynthia Zaitz, in her sky-blue Pinto.

I was 21, Cynthia was only 17 and neither of us had been to New Mexico

before. But as I breathed in the dry, high-desert air and gazed across

the small city to several jagged volcano cones on the horizon, I felt

immensely happy. Over the next few days we found a small apartment near

the university and quickly landed part-time jobs. Then one wickedly hot

summer afternoon, portfolio of prints in hand, I found my way into the

lithography studio in the basement of UNM’s old Fine Arts building. No

one was around other than a strong looking man with thick black hair who

was rolling ink onto a stone. The basement was hot and he had stripped

down to a sleeveless cotton undershirt.

“Excuse me,” I said, “I’m sorry to

bother you, but are you Garo Antreasian?” Like every lithography

student, I knew that Garo Antreasian was one of the country’s most

distinguished fine art printmakers. He had founded the Tamarind

Institute of Lithography in Los Angeles in 1960, becoming its first

Technical Director, before moving to Albuquerque in 1964 to join UNM’s

art faculty and head its litho department. Some years later in 1971, he

and Clinton Adams would write the definitive book on creative

lithography called "The Tamarind Book of Lithography: Art and Technique".

Garo laid the large roller in its

carriage and gave me his full attention. I introduced myself and said

that I had just graduated from USF, where I'd worked mostly in litho and

I was hoping to get into UNM’s graduate school. Garo said he respected

the program at USF and knew many of the people I had worked with in

Tampa. His deep voice and measured words resonated in the quiet shop.

Despite the sweaty t-shirt, Garo was clearly a man who commanded

respect.

“Let’s see some of your work,” he

said pleasantly, pulling a metal stool up to one of the long grey

tables. I spread out the lithographs I had made in Florida: surreal

images of children in bathing suits wandering inexplicably through high

mountain tundra, the nude back of a young woman emerging from a textured

gray wash, and some large etchings of enigmatic shapes floating high

above the earth. As always, I felt incredibly uncomfortable showing my

work, which I suspected wasn’t very sophisticated.

Garo was kind but direct. “These are

very well printed,” he said. “But you won’t get into graduate school

with this body of work.” His words came as no surprise, yet for some

reason I didn’t feel crushed. He studied me for a moment and then said,

“Tell you what, why don’t you sign up for my Litho class in the fall.

You don’t have to be part of the program to do that. Take my class and

let’s see where it goes.”

Not surprisingly, Garo turned out to

be one of the finest instructors I ever had. As an artist he was a

superb and innovative printmaker whose complex, eye-dazzling

abstractions were setting both style and standard in that era. He was

also an avid educator who not only lectured about printing techniques,

but assigned his students papers to write about the great printmakers of

the past. My first assignment was to write about Richard Parkes

Bonington, Eugène Isabey, and Eugène Delacroix, all 19th century artists

whose fine draftsmanship and eye for picturesque beauty had generated a

new art market for lithographs of exotic subjects. Delacroix, I learned,

was an artist immersed in dark passions who lived to tell the tale,

unlike his contemporary Théodore Géricault, who painted severed human

heads on his kitchen table, along with the monstrous “Raft of the

Medusa” that hangs in the Louvre, but was dead by 33. I could understand

these romantic artists, and would have loved to emulate their lives and

imagery. Trouble was I was living in 1975, not 1850— and art had come to

have far different meanings and appearances. Nonetheless, thanks to

Garo’s encouragement, I was one of only a few students accepted into the

M.A. program the following semester.

♥♥♥♥

While I coped with the challenges of

UNM’s graduate program, Mark was learning to be a professional printer

at Gemini. We started exchanging letters, talking honestly and openly

about making a go of it in our new surroundings, our botched romances,

and the art we were trying to produce. Mark’s loose, elegant penmanship

was a visual delight and though he insisted he was slightly dyslexic and

not very comfortable putting thoughts into words, he was actually a fine

writer. His letters, fluid in appearance and narrative, provided an

intimate picture of a young man absolutely determined to become a great

artist. He wrote to me about the images he was creating, ideas bursting

from his imagination, and after two and a half years, his decision to

leave Gemini to concentrate on his own art. As the years passed he

described financial uncertainties, a string of passionate, mostly

short-lived love affairs, celebrations when his art sold and there was

money to burn, collaborations with LA’s ballet, dance and theater

companies, and the vicissitudes of being represented by a prestigious

New York gallery. A constant theme was his deep affection for Los

Angeles and his artist friends. He was never so content as when working

on a painting as the rain poured down outside his cavernous studio. It

was a sound he never tired of.

Mark set extraordinarily high

standards for himself and expected the same of his fellow artists.

Unable to match his ideals they often disappointed him. Running through

his letters was a clarion call to achieve great things in art and not

become distracted from the path. Three times in three different letters

he quoted Marcel Duchamp’s admonition that a true artist will forgo

family and friends for the sake of art. Mark agreed about staying clear

of marriage and children, though he wasn’t so sure about sacrificing

friends. Mark’s friends were his family and he remained steadfast to

many of us to the end.

Having spent a couple of semesters

trying to adapt to UNM’s grad program, I found myself floundering,

confused, and threadbare. Everything I thought I knew about art was

being challenged by instructors whose sensibilities were totally outside

my experience and emotional makeup. My committee was made up of

middle-aged men, some of whom were devotees of Abstract Expressionism.

Making sense and meaning out of non-objective work was turning out to be

a terrible struggle, though I’d been doing my damnedest to push past my

limitations. It was especially troubling to think I was letting Garo

down; that maybe I was turning out to be a bad bet.

In the summer of 1977 I drove to LA

to visit Mark, who was still printing at Gemini. My old roommate,

Cynthia, had moved there and was living in an apartment not too far from

him, so while she was at work Mark whisked me around the city in his old

blue VW, eager to show me the sights and talk about old times. He was

very thin, more hyper than in the past and even more good looking.

Living so close to Hollywood, his old obsession with Charlie Chaplin had

only intensified, and so my tour included all the Chaplin landmarks:

houses the Little Tramp had lived in, his old film studio, streets where

his movies had been shot, his actresses’ homes (some of whom were still

living), theaters where his films had premiered, right down to (as I

told my mother later) Charlie Chaplin’s favorite manhole cover.

We ended up in the Hollywood hills,

Mark gunning the engine up narrow, twisting roads past

bougainvillea-covered walls concealing Spanish-style bungalows, to the

parklands just below the giant Hollywood sign. He was fascinated by the

sign and would eventually create a body of enormous art works inspired

by it. To me, the scrubby hillside with dirt trails meandering through

the dry grass felt like the last shred of the natural world. As we gazed

over the city, Mark told me about a lovely young woman he had recently

fallen in love with who he had wanted to impress. For their first date

he had invited her to dinner at an upscale restaurant. Being youthful

residents of glitzy Los Angeles, they had both dressed to the nines, she

in a shimmering evening gown, he in a white linen suit and fedora. But

first, suggested Mark, in his velvet-soft voice, why not take a

moonlight drive into the Hollywood Hills and look at the city lights for

a bit. Oh, what a lovely idea, Mark, the poor innocent must have

simpered. So up the winding road they went under a brilliant full moon,

until they climbed above the suburbs and parked on the windy hillside

near one of the trails snaking through the dark undergrowth. Mark cut

the engine, turned to his beloved, and suggested that they walk up the

trail a little ways to get a better view. Smitten by the handsome

artist, the young lady gingerly set her high heels on the dirt path,

clutching her dress so it wouldn’t snag on the brambles. A few steps

further and— lo and behold, in the darkness ahead — a twinkling light.

Why, what is that? said Mark in a perplexed tone, gently pulling the

girl forward, as she was starting to back away from the thought of

potential ax murderers. Mark, she said tremulously, maybe we should turn

around? But Mark was insistent. Just a few steps more, he insisted. Then

around a bend something improbable came into view — a table covered with

a white cloth, glowing candles, and a single rose in a vase. Most

spectacularly, standing beside the table, was a stone-faced,

slick-haired butler, with a white napkin folded over the arm of his

impeccable uniform. Mark’s date burst into nervous tears as the butler

pulled out a chair for her, popped the cork on the champagne, and

proceeded to discreetly serve the couple shrimp appetizer en plein air

as the moonlight shone on the looming letters of the Hollywood sign.

It took me a long time to close my

jaw after hearing this story. I couldn’t help but think that it would

take a most remarkable woman to keep up with Mark Stock’s effusive brand

of romance.

The next day was Sunday and since

Gemini was closed Mark gave me a tour of the pristine facility filled

with state-of-the-art presses. The printers were currently working on a

Jasper Johns series called “6 Lithographs (after Untitled 1975)”. Jasper

Johns, as I well knew, had long been regarded as one of America’s most

influential and important artists. I studied the prints, literally “hot

off the press,” that consisted of fields of colorful crosshatches and

flagstone-like shapes. Each print was related to, yet subtly different,

from the next, as if Johns was manipulating the deceptively joyous

pattern in various ways that contradicted itself. Not only was he

playing a complex intellectual game by arranging and rearranging strong

visual elements, he was also raising philosophical questions about

patterns, expectation, and unpredictability. And beneath that cleverness

I sensed something emotional driving the whole process, even though

Johns, a master of camouflage and deflection, kept that mysterious

component well hidden.

Seeing those prints kicked my

artistic circuitry into high gear. Back at UNM, inspired by a new vision

of how abstraction could be intellectual, playful, and emotional at the

same time, I buckled down and produced a series of large abstract

lithographs. Against dark gray or black backgrounds that could be

perceived as either solid or atmospheric, strong-colored shapes

interacted with game pieces stamped with enigmatic symbols that I had

seen on an old mahjong set. Garo’s influence was evident in the

technical virtuosity it took to print the editions, and in the use of

“rainbow rolls” of color. Most importantly, the imagery corresponded to

hard realities that I was grappling with in life: chance, change,

unpredictability, and luck. Somewhere in my readings I had run across a

remark by Marcel Duchamp along the lines of: There is this thing we call

luck, but your luck and my luck are not the same. Thanks in large part

to Mark’s kindness, I graduated in 1978 from one of the most difficult

printmaking programs in the country, having produced a body of art work

to be proud of.

In LA, Mark was painting gigantic

canvases in an absolute whirlwind of energy. Once an idea had captured

his imagination he didn’t let it go until he had made an entire series

about the subject. He had developed a lush, painterly style that

harkened back to John Singer Sargent, but whose color palette had all

the vibrancy of Pop Art. Each highly realistic painting resembled a

pivotal moment in a movie or play where some disquieting truth is being

revealed. Illuminated by warm lights or cloaked in dark shadows, men in

tuxedos and begowned women spied on each other through parted curtains,

doors or windows. Other subjects that intrigued him were suicide, crimes

of passion, loneliness and heartbreak. Composed with dramatic

chiaroscuro lighting, the scenes were part George de la Tour and part

Caravaggio with a big dollop of Alfred Hitchcock. At the same time, Mark

was designing billboard-size stage sets for dance companies, posters for

film festivals, and hobnobbing with film makers and professional

magicians.

♣♣♣♣

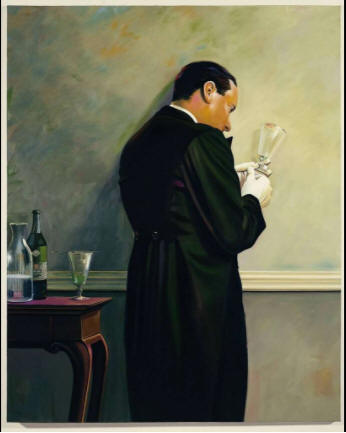

Photo: "The Butler's In

Love" from the collection of Bix Restaurant, San Francisco, California,

courtesy of Modernism Inc., San Francisco.

One of the paintings from his series

“The Butler’s in Love” inspired a short film by David Arquette

(available on YouTube), in which Mark appears briefly as a magician;

sophisticated magic tricks having become yet another talent he was

perfecting. “The Butler’s in Love” was to become the iconic image Mark

was best known for, and he painted many variations of a butler who falls

in love with the woman who employs him. Her station in life is far above

his, she doesn't know he exists, or else she is attracted to him, but

trapped in a world of money and privilege; thus, the butler’s helpless

muteness and unrequited longing. His outpouring was nonstop and his

colorful canvases filled the walls of galleries and museums. Mark was

turning out to be a hugely complex human being: enormously talented,

ambitious, theatrical, funny, enthusiastic, charming to the nth degree,

but also someone driven by some very strange undercurrents.

Like Mark I had shifted from

printmaking to painting as my life had gone through many permutations:

working at an art gallery in Dallas, teaching art at TCU in Fort Worth,

traveling to Europe several times, earning yet another graduate degree,

writing and illustrating the book "Chimayo Valley Traditions", and

producing a line of cards under the business name Pythea Productions. By

1986, I had moved to northern New Mexico to live with a man I would

marry and spend the rest of my life with. When I wasn’t painting I was

making a living selling masterworks of photography at the Andrew Smith

Gallery in Santa Fe.

1999 through 2000 was a time of

significant recognition for both Mark and me. Mark had every reason to

be extremely proud of the lavishly illustrated biography, “Mark Stock:

Paintings” by Barnaby Conrad III, (2000), a book that left no doubt what

a brilliant artist he was. Around this same time, a young photography

curator named Shannon Thomas Perich, working at the Smithsonian’s Museum

of American Art, had picked up a card I had made of one of my paintings.

On the surface Santo Pinholé looked like a traditional New Mexican

retablo of a saint, but Shannon quickly decoded the visual reference to

Ansel Adams’s “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” along with the card’s

tongue-in-cheek puns about the history of photography. In 1999, she

designed a showcase on the museum’s first floor that displayed Santo

Pinholé, alongside a 19th century New Mexican retablo of San Ignacio

(patron of teachers), and an original Ansel Adams print of “Moonrise.”

Other display items informed the public about the history of the

photographic process and the tradition of icon-making in colonial New

Mexico. It was the first and, no doubt, only time that Ansel Adams, the

history of photography, and the cult of New Mexico saints would

cheerfully occupy the same space.

Mark was delighted for me, if a bit

baffled by how such a small painting could have generated so much

attention. I couldn’t have agreed more, and privately chalked up the

Smithsonian exhibit to a spectacular stroke of Duchampian luck.

After 2000 our exchanges grew a

little more infrequent. But even after Mark moved his studio to Oakland,

he never stopped sending me personalized invitations for his shows, all

of which I saved. In 2010 I called him to say I was making a trip to the

Bay Area and hoped we could see each other. He was thrilled about the

reunion and we made plans to spend an evening together. “But Liz,” he

laughed in that gentle, self-effacing way I knew so well. “I’ve changed.

You won’t recognize me.”

When a friend dropped me off at

Mark’s two-story condominium in Oakland, not far from Pixar Studios, he

was waiting outside to greet me. The youthful, lithe man I remembered

from 35 years ago had vanished. Mark was nearly bald now, heavier, and

he even seemed taller than I remembered, although that couldn’t be

possible. But his soft voice and kind eyes were the same, as was the

hospitality he radiated, along with his eagerness to tell me absolutely

everything about his life.

We sat in his handsome Oakland home,

its high walls covered with art works illuminated by afternoon sunlight

filtering through a twenty-foot window. The window was flanked by heavy

floor-to-ceiling curtains, so it felt a little like being inside an old

movie house, especially as the music playing quietly in the background

might have been the soundtrack from an eerie suspense film. I smiled to

myself. I was once again in Mark’s theater where anything could happen.

“Do you like my walls?” asked Mark as

he poured drinks into a couple of fluted glasses. I walked over to feel

the dark wood and instantly knew that every single panel, hundreds of

them, had been painted by Mark to look like wood. As we sipped drinks

and caught up on our lives, he told me that he had finally found what he

had always longed for: a solid, loving relationship with a woman named

Sharon Ding. He talked enthusiastically about his life with Sharon,

their travels, and their beloved pet beagles. Although Sharon lived and

worked in Los Angeles and he was in Oakland, they saw each other

regularly and had been together for nine years.

In his home that evening, and later

at his downtown gallery Modernism, Mark dazzled me with a few uncanny

magic tricks. “Pick a card,” he said, fanning the deck in his large

hands. As I picked out the 4 of Spades he handed me a felt tip pen. “Now

Liz, would you please write your name on the card.” I scrawled Liz Kay

over the card and then inserted it back into the deck that he held out

to me. Mark shuffled the deck for a few seconds. Suddenly he tossed all

the cards into the air. They fluttered over our heads and fell randomly

at our feet. “Look up!” he said. “Is that your card?” Stuck to the

ceiling high above us was the 4 of Spades with my signature scrawled

over it. I had absolutely no idea how he had done this, nor would he

tell me.

As we were leaving his house, he

pointed out a gold frame hanging on a dark green wall opposite the front

door. There was nothing in the frame, just the green wall behind it.

Then Mark bent forward and turned a virtually invisible door knob. “This

is where I sleep,” he said. The small room had a bed in it cluttered

with magazines, papers, books, clothes and photographs. He was using it

as a storeroom at the time, because with the downturn in the economy he

was having to give up his studio. He had already moved his paintings

into his garage, and his possessions were in chaos. Maybe it was the

uncanny card trick, or the creepy music, but I felt more than a little

relieved as we left the condominium. If there was ever a hidden door

behind which to hide a body, I had just been in and out of it.

Mark had become an absolute pro with his magic skills. In downtown San

Francisco we entered a skyscraper and took an elevator up to Modernism,

where an opening was underway. After he introduced me to gallery owner,

Martin Muller, and we had looked at his most recent series of trompe

l’oeil paintings, Mark asked if I would indulge him in just one more

magic trick. This one involved my thinking of a number between 1 and 100

(I thought of 95), and his not only guessing it, but showing it to me

written on the inside of his palm: a trick that made the synapses in my

brain freeze in a “this can’t be happening” moment. Out of the corner of

my eye I watched the staff at Modernism gleefully enjoying my stupefied

reaction. Clearly, Mark the Magician had become as legendary as Mark the

Artist.

From Modernism he took me to see his

painting “The Butler’s in Love -- Absinthe”, the great centerpiece of a

swanky San Francisco restaurant called Bix. The massive painting of a

melancholy butler contemplating a cocktail glass with lipstick marks on

its rim, hung above the piano where a jazz singer was crooning to the

fashionable crowd.

It was pushing 9 o’clock as we walked

through the heart of North Beach, San Francisco’s oldest quarter, whose

faded brick walls had withstood earthquakes and fires and whose frontier

coffers had once been stocked with gold and whiskey. Mark recounted the

district’s history as if he had been witness to it all, just as decades

earlier he had taken me all over Charlie Chaplin’s Hollywood, pointing

out buildings and theaters made famous by the Little Tramp. It was the

same consummate performance I had seen the beginnings of 35 years

earlier in Lutz.

In a quiet Italian restaurant

(“Mark!” greeted the owner, clapping my friend on his shoulder and

leading us to a special table), we talked for hours about the past,

retelling stories about our old friends Theo Wujcik, John Ludlow and

Cynthia Zaitz, and sharing the trajectories of our lives since our USF

litho shop days.

“You’ve always been like a sister to

me,” said Mark warmly as we hugged goodbye on the doorstep of my

friend’s house.

After I came home and to my utter

astonishment, he sent my husband Raymond and me a painting as a gift: a

framed oil of the 4 of Spades with my signature. This generous, kind,

extraordinary man had titled it, “A Souvenir from My Ceiling.”

♠♠♠♠

Only a few weeks before Theo

Wujcik, by then age 78, died of cancer in Tampa on Saturday, March

29, 2014, Mark had flown to Florida to visit him. When they said

good-bye Mark surely knew it was for the last time. But who could have

dreamed that Mark himself would die suddenly from heart failure on

Wednesday, March 26, 2014— 4 days before Theo died.

I was stunned and profoundly saddened

by the news of both deaths, but especially by the loss of Mark.

Tragically, I learned from Sharon Ding, that Mark had died just before a

new exhibit of his work was due to open at Modernism. Sadder still, he

and Barnaby Conrad had been making plans for a second book. It was

distressing beyond measure to know that Mark had been snatched out of

life so abruptly and with so much yet ahead.

As all this was happening, Raymond

and I were on the point of leaving for Germany on vacation. I had been

there before, but this time I was looking forward to seeing the country

near Hamburg. My mother’s ancestors had immigrated to America from that

area in the late 1800s. Knowing that Mark had been born in Frankfurt to

American parents stationed at a military base, I determined I would take

something in his memory to the country of his birth. Modernism had just

sent us an announcement of his death with his painting “Sunset,” 1989,

on the front. I decided to take it with me and leave it somewhere in

Germany— perhaps toss it in a river.

In Berlin we discovered that our

friend Lars-Olav Beier, who we were staying with, lived next to a large

cemetery. I knew immediately that this would be the perfect place to

leave Mark’s announcement, a decision that was solidified when Lars’s

father, Lars-W. Beier, who lived in Münster, sent an email encouraging

us to visit the cemetery because so many of Germany’s great citizens

were buried there.

On our second morning in Berlin I put

Mark’s announcement in my purse and after breakfast, Raymond and I left

the apartment, walked a block and entered Luisenstädtischer Friedhof

through a stone gateway. It was a cool spring day. Puffy white clouds

drifted in the blue sky above chestnut trees laden with pink blossoms.

We followed a gravel walkway bordered by lush green grass sprinkled with

wild flowers. Masses of purple lilacs bloomed next to ivy covered stone

walls, and everywhere trees and bushes were bursting with sweet smelling

flowers. Some of the statues seemed to be reaching for the blossoms, as

if trying to smell them. It was, without a doubt, the most beautiful

cemetery I had ever seen.

We had walked only a few yards when I

stopped in my tracks and said to Raymond, “I don’t believe this.” We

were standing in front of a large family memorial with a

larger-than-life statue of a young man with his hand over his forehead.

The name carved above the statue was “Robert Stock.”

Now, I did not think for a minute

that I had found Mark Stock’s long lost German ancestors. As far as I

knew, Mark didn’t have any German ancestry— this was just an

extraordinary coincidence. Nonetheless, the statue standing in the pose

of a weary worker wearing an apron, his arm bent over his forehead,

looked almost exactly like a photograph of Mark taken in Gemini when he

was printing for the artist, Roy Lichtenstein. Raymond and I marveled at

this uncanny connection for a long time before continuing to explore the

cemetery.

Wandering up and down the paths, I

photographed the graves, statues and plants. Then, as we headed back

toward the Stock memorial, it seemed that the quality of the air changed

subtly, as if the barometer pressure had become heavier. My steps

slowed; it felt like I was moving through water permeated by gentle

sadness. Probably I was just tired, but the sensation was so strong that

I described it to Raymond, who said he wasn’t aware of anything unusual.

Back at the Stock memorial I carefully placed the card with Mark’s

painting “Sunset” at the foot of his doppelgänger. The next morning I

returned with a bouquet of lilies-of-the-valley and laid them beside the

announcement.

That should have been the end of the

story— my humble tribute to my old friend at the grave of the unrelated

Family Stock. After I came home I did a little research and learned that

Robert Stock (1858-1912), the actual inhabitant of the grave, was a

brilliant inventor and entrepreneur, who rose from humble roots to

become a sort of Henry Ford/Thomas Edison of Germany. If I read the

awkward English translation correctly, he appears to have invented the

German telephone system!

Then one more piece of information

fell into place.

I emailed the description and

photographs of the cemetery to Sharon Ding, who passed it on to Mark’s

brother, Don. In an email Don said that in fact, his and Mark’s

ancestors had come from Germany, from the town of Dettingen. I looked up

Dettingen on a map and discovered that it lies only about 85 miles from

Munich— where Alois Senefelder invented lithography.

So my small part in Mark’s life ended

in his ancestral homeland, in a stately cemetery where Germany’s

celebrated citizens are buried and whose atmosphere had all the beauty,

uncanniness and melancholy that Mark infused into his paintings. It’s

all so quirky that I’ve even wondered if Mark didn’t somehow have a hand

in it. In any case, I know one thing for certain— if Mark was still here

he would have turned it into art.

~E. A. Kay - © March 2017

There is a video at

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=eSYOAPmiBus of Mark Stock discussing

the image on this tombstone.

PHOTO LEFT:

Liz visiting Mark’s grave at the Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena,

California

RELATED LINKS WORTH VISITING:

Additional information on Mark Stock can be

found at

http://www.theworldofmarkstock.com/bio.htm.

Additional information on Elizabeth A. Kay

can be found at

http://www.pytheaproductions.com/exhibitions.html.

Additional information on Theo Wujcik can

be found at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theo_Wujcik.

Additional information on Garo Antreasian

can be found at: https://www.antreasian.com |

RARWRITER PUBLISHING GROUP PRESENTS

RARWRITER PUBLISHING GROUP PRESENTS RARWRITER PUBLISHING GROUP PRESENTS

RARWRITER PUBLISHING GROUP PRESENTS